Muggy Mugaseth might be the answer to the trivia question of who was the first international student-athlete to play intercollegiate squash.

The cover of Squash: A History of the Game features a photograph of the 1951 Harvard men’s squash team. Standing next to a six foot five David Watts is Jehangir Mugaseth. Known as Muggy, Mugaseth was a diminutive but brilliant cricketer from Mumbai, India in the class of 1952. In May 1951 in the Manchester Guardian, Alistair Cooke covered a Harvard v. Yale cricket match played in Boston. Mugaseth, Cooke wrote, was a “supple young man from Bombay who had one of those long, beautiful unwinding runs” up to bowl the ball.

Mugaseth anchored the Harvard squash team his junior and senior year. Jack Barnaby, his coach, called him “a stylist.” He played eight on the ladder and was a big reason why Harvard captured its first official national intercollegiate team title in 1951.

Since then overseas squash players always been a part of the U.S. collegiate scene. In the hardball era, it was not uncommon. North Americans always played for U.S. teams: a half dozen Canadians won the men’s national intercollegiate individual title in the hardball era, and the only family to have both a brother and a sister win the individual title are the Fraibergs from Montreal, Jordanna and Jeremy. Sometimes Mexicans like Rudy Rodriguez at Penn came north. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the three Gonzales cousins from Puerto Rico, Jaime, Jose and Fernando, played for Harvard.

Asia was another regular source. The 1991 Dartmouth men’s team, which I played on, claimed top-nine players from Hong Kong, India and South Korea. Harvard and Yale boasted numerous players from India, including the Ezra and Pandole brothers and Cyrus Mehta. Penn had Anil Kapur and Dinesh Nayak in the 1970s. Pakistan gave Arif Sarfraz, who played at Princeton in the 1970s. Israel was another supplier: Johnny Kaye and Tal Ben- Shahar both played at Harvard in the early 1990s.

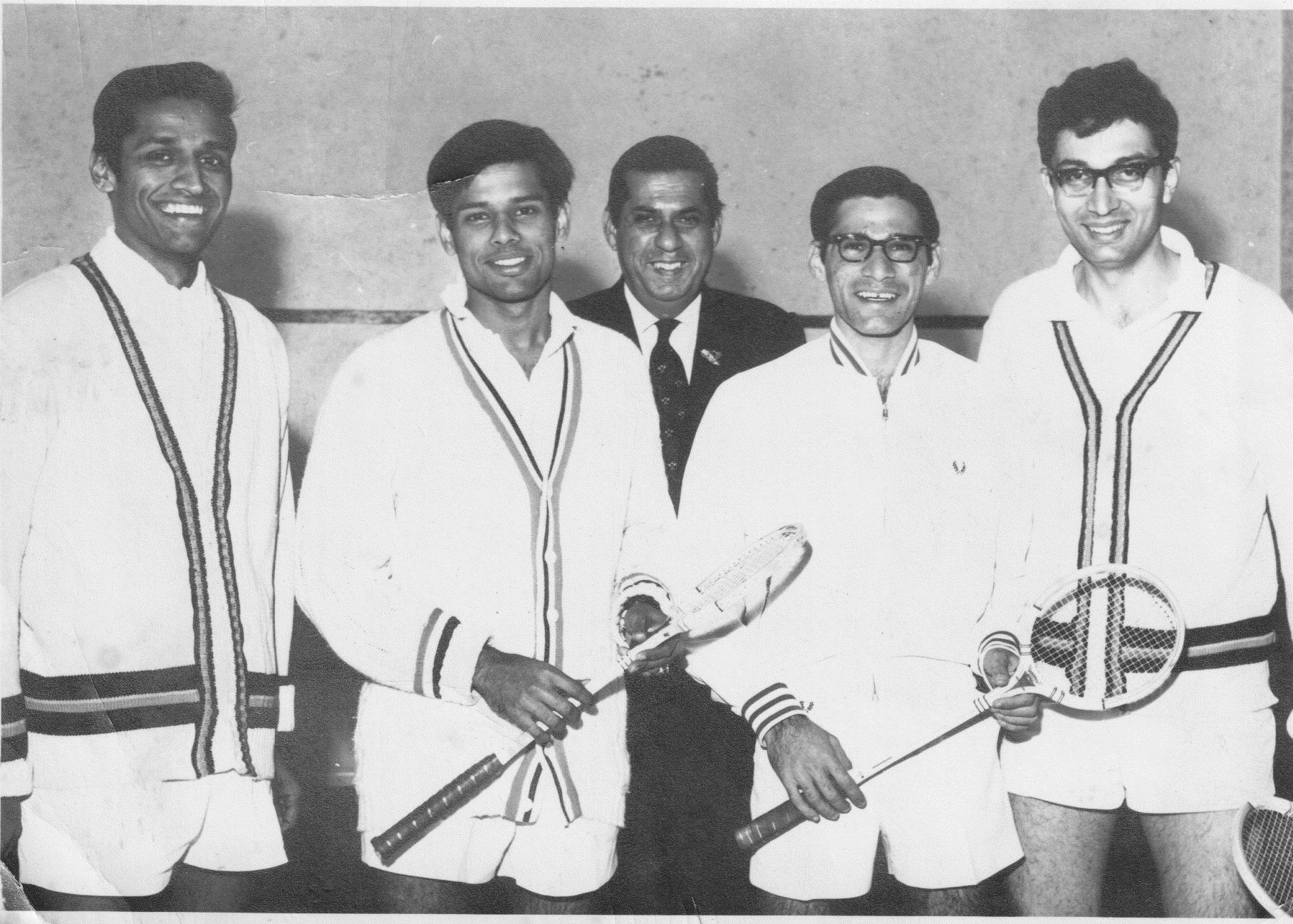

But it was always hopscotching through happenstance. Before the Internet and email, luck played a big role. The most famous international recruiting story is Anil Nayar, the future U.S. Squash Hall of Famer. From Mumbai, Nayar had won the British Junior Open U19 title in 1965 and wanted to study at Harvard. His coach in Mumbai, Yusuf Khan, wrote to Mo Khan, the pro at the Harvard Club in Boston. Mo Khan wrote back, asking for a letter. Nayar wrote a letter in Pashto to Mo Khan, who translated the letter and handed it to Eric Cutler, an admissions officer at Harvard and a squash player (he later assisted with the women’s team at Harvard and coached squash at Noble & Greenough). Cutler wrote a letter to Nayar, asking him to take the SATs. Nayar wrote back, sending his results. Cutler mailed an admissions form. Nayar sent it in. Then in June Nayar received a telegram from Harvard, saying he had been accepted. Think of all the things that had to go right—and all the letters back and forth across the globe.

Nayar dutifully arrived on campus in September. At an orientation event, he met the squash coach, Jack Barnaby. It turned out that Cutler had never told Barnaby about Nayar’s admission, either because he forgot or because he wanted to play a joke on him. Anyway, Nayar introduced himself and said that he was a squash player. Barnaby didn’t register who Nayar was. The next day, Nayar went to Hemingway Gym, where the squash courts were, and repeated to Barnaby that he was a squash player.

Barnaby told him to go hit some balls. Dinny Adams, a senior and No.1 on the team, walked into Hemingway. The custodian at Hemingway told Adams that there was some freshman from India in court three, the lefthanded gallery court, who could really smack it. Adams watched for a few moments of Nayar soloing, and then he went to Barnaby’s office to fetch his coach. Barnaby watched. He finally asked Nayar about his squash resume: out came the fact that Nayar had won the national title of India and the BJO.

“I don’t have the red carpet here today,” Barnaby famously said, “but I’ll have it tomorrow.”

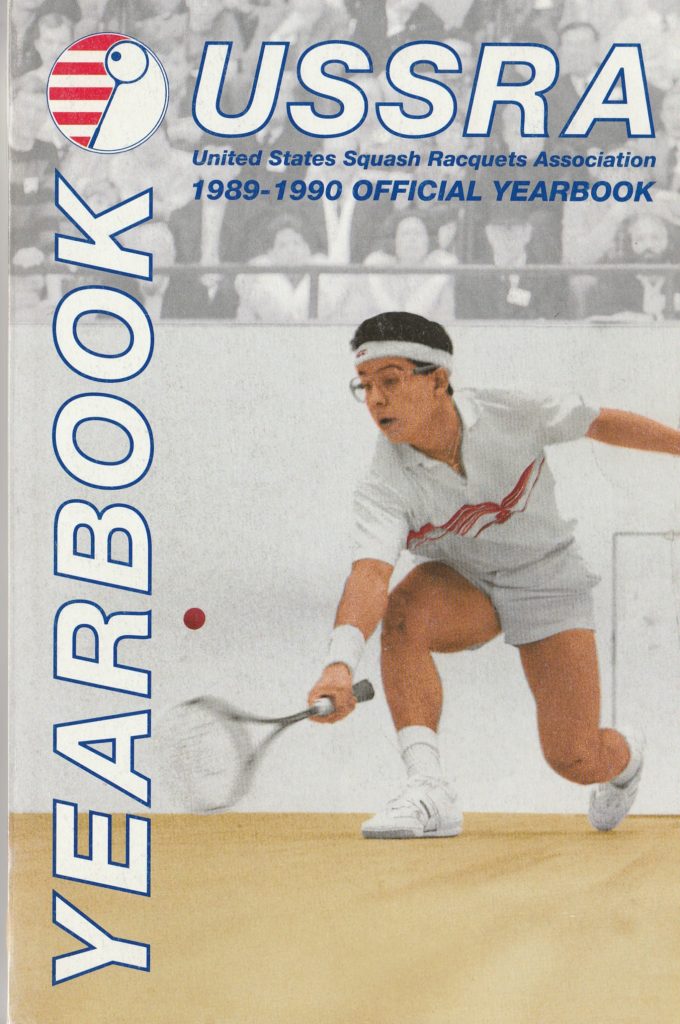

Red carpets started to roll a quarter century ago, when intercollegiate squash switched from hardball to softball—the women in the fall of 1993 and the men in the fall of 1994. It was as if America had only played tennis on red clay and now had gone over to grass-court tennis, so now all the world’s grass-court players could seamlessly play college squash.

the Ivy League Squash Athlete of the Year.

It was easy to pin-point the school in the vanguard: Trinity. The Bantams started deliberately bringing in international squash student-athletes in 1996. The first man was Marcus Cowie, Trinity 2000. When he arrived in Hartford, Wendy Bartlett asked him about any Englishwomen he would recommend. He mentioned Gail Davie and in January 1997 Davie matriculated. Then a cascade: players from more than two dozen countries, a slew of national championships and the men posting a 252-win streak. Sometimes Trinity’s entire top nine were international students.

The internationalization of collegiate squash was bumpy. The parents of American juniors grumbled loudly about precious roster spots being taken up by non-Americans. Although other schools were accelerating their recruiting, Trinity was the poster child. In March 2004 the Harvard Crimson dubbed Trinity the Evil Empire. Fans screamed nasty epithets, sexual vulgarities and xenophobic curses at Trinity players. Once at a dual match, fans held up signs saying, “They might be national champs but they can’t speak English.” Of course, the reality was far different. The Trinity students were good students, with the team’s GPA usually higher than the student average and at the top of all Trinity’s teams. Only one overseas recruit at Trinity never graduated from the program. Moreover, the players were not hired mercenaries who returned from whence they came: after graduation, most of them stayed in the U.S. squash community, working as coaches and teaching pros and joining the professional singles and doubles tours.

Some top-ten programs today barely do it—in recent decades, Dartmouth has had just one player not from North America—but overseas players have filtered into many varsity programs, not just the very best but some ranked in the teens and twenties and even thirties. Moreover, a few programs—Drexel, George Washington, Stanford and Virginia (but not Trinity, as often claimed)—offer athletic scholarships that usually go to international students.

Nowadays, international recruits are just a part of the system. Like with so many changes, young Americans find the internationalization quite normal. In fact, for most, it is a boon. Fifty-two countries send a student-athlete to a U.S. collegiate squash team—this is not simply an influx of players from one nation. The Americans learn about other cultures, other ways of viewing the world. They travel to their teammates’ home cities. They go to their weddings. If college is supposed to be about broadening your experience, what better way than to forge deep, abiding friendships with people not like you? For me, I loved learning more about my teammates’ countries. Indeed so much learning happened at Dartmouth that my teammate from India, Raman Narayanan, delighted in spoofing on the American taste for the exotic. He’d fool the freshman by telling them he came from a village where everyone’s name was a palindrome.

A consequence of the recruiting is that the level of play has jumped considerably. Many of the best young players in the world play collegiate squash. This in turn has directly helped Team USA. Our players, whether Julian Illingworth in the mid-2000s or Amanda Sobhy a decade later, benefited from competing against world-class talent while in college.

“The influx of international squash student-athletes has greatly benefited many college squash constituents,” said David Poolman, the executive director of the College Squash Association. “The on-court competition is very exciting, with varied styles on display and the standard of play improving every year. Our member schools’ communities and athletics departments gain an added element of diversity, which can help strengthen and refine their campus cultures. The international students gain access to a phenomenal education and a potential home away from home, while domestic students can expand their horizons socially, culturally, and physically through relationships with foreign teammates. It is a testament to both the college experience and the intercollegiate squash experience that top junior players from around the world want to play for four years in the CSA.”

Squash has not undergone this transition in a vacuum. The global forces that prompted the switch from hardball to softball were the same forces that affected higher education in general. Starting in the late 1990s universities renewed an effort to diversify their student body and have a more global outlook. Counting not only how many U.S. states their student hailed from but how many countries, they started seeking out students rather than just letting them come a la Nayar.

In this century, the percentage of international students has skyrocketed. In 2000 Mount Holyoke was 13% international; in 2014 it was 28%. In the same period, Harvard, the university most well-known overseas, went from 7% to 13%. Colby went from 6% to 15%. Columbia went from 7% to 17%—in 2014 it had nearly 12,000 international grad and undergrad students on campus, the third highest raw number in the country. In 2019 the student bodies of most universities with a varsity squash team were at least 10% international. The leader was Rochester, which was 27% international.

Squash is exactly like other NCAA sports. International student-athletes are now a central part of the U.S. collegiate sports story. One hundred and ninety countries sent a student-athlete to U.S. colleges in 2018: for example, Afghanistan sent one and Zimbabwe sent sixty-two.

Division I sports are filled with international kids. American varsity squash teams are about a quarter international (27% to be exact); players hail from fifty-two other countries. Some sports have even smaller percentages. In 2018 Division I collegiate baseball teams had seventeen countries of origin, but outside of Canada (with 101) and Puerto Rico (with twenty-three) none of those fifteen other countries sent more than five—while the U.S. provided 7,379. So just 2.1% of baseball players are overseas kids.

How about Division I tennis, perhaps our most analogous sport? In 2018, women’s tennis players came from 106 countries. The U.S. supplied 1,059; the other nations gave 1,423. That is 57.3% from overseas. In 2018, Division I men’s tennis players came from ninety-eight countries. The U.S. supplied 820; the other nations gave 1,392. That is 62.9% from overseas. (Spain sends the most tennis players.) Thus, tennis has twice as many countries represented on their teams as squash and well more than double the percentage of overseas players.

Golf is more closely in line with squash. For Division I women, there are sixty-seven nations. The U.S. supplied 1,368; the others gave 642. That is 31.9 from overseas. For Division I men, there are fifty-one nations. The U.S. supplied 1,929; the others gave 567. That is 22.7% from overseas. (Canada sends the most golfers.)

Other Division I sports are the same. Who knew that women’s bowling attracted bowlers from thirteen nations? Who knew that men’s soccer is nearly 40% from overseas? Who knew that crew is so diverse, with forty nations sending rowers for women’s teams? It is not despite g lobalization but because of globalization that Americans will continue to be relevant in collegiate squash. The number of countries sending students to play collegiate squash will probably rise but the percentage has steadied around a quarter and will probably remain there for some time. More schools are creating teams, so as collegiate squash expands, Americans will probably fill most of those roster spots in part because American juniors—unlike in tennis—are among the best in the world. They are the best in the world because they travel to tournaments in Europe, attend camps in Africa and train in the Middle East. And because the world comes to the States. Remember a quarter century ago when only a half dozen nations sent players to the U.S. Junior Open?

“Strength through diversity is one message I recall from my days at Cornell,” said Kevin Klipstein, the president and CEO of US Squash. “How else would we expand our worlds? The squash community is a reflection of our larger world. To have such a diverse group of players in college squash is invaluable to the sport in the U.S. for a host of reasons, including competitively, and more importantly, enriching every athlete’s life through these deep interpersonal connections which last a lifetime.”