by James Zug

When we emerged from immigration, baggage claim and customs, it was like an explosion. A swarm of people called our names. Signs. Cameras flashed: selfies, a professional photographer snapping from all angles. Greetings, handshakes, hellos. Autographs.

It was a damp, chilly afternoon at Boryspil International Airport in Kiev, Ukraine but inside the arrivals terminal emotions were running high. This was a big deal: the World Squash Ambassadors had landed.

There was some attention for Andrew Shelley, the executive director of the World Squash Federation and handshakes for others in the entourage, but most of the fuss was focused on Ramy Ashour and Camille Serme.

“The ambassador tours are predicated upon having the best players because they are the star attractions,” Shelley said. “They give us the foothold. The reception at the airport is proof. These tours have been immensely important from my point of view. They are about generating local enthusiasm for squash, for inspiring current players and for creating new players, for promoting squash so it gets attention and a real boost in local media and for solidifying partnerships with local influencers.”

As our ten-car convoy left for Kiev, we marveled at the power of squash to bring people together.

The ambassador tours originated in a chance meeting at the Pyramids of Giza. In the early 1990s Tom Tarantino, a Philadelphia real estate investor who picked up squash while at Penn Law School, had gotten hooked on softball squash. He launched the Philadelphia Open, a pro softball event for men and women, with equal prize money. Tarantino ran it for a half-dozen years, starting at Cynwyd Club (the first club with a softball court in the area) and then around the city to clubs like the Racquet Club of Philadelphia, Germantown Cricket Club and Berwyn Squash & Fitness as they converted courts. The tournament struggled, as they sometimes do, from donor fatigue, political infighting and buck-passing.

In 1998 Tarantino went to the Al Ahram tournament at the Pyramids. One afternoon he and a friend, John Schellenberg, were playing on the portable court before the evening’s matches were to begin. Andrew Shelley came past. The executive director of the women’s pro tour, the Women’s International Squash Professional Association (WISPA), Shelley had talked with Tarantino on the phone but never met. “We hit it off,” Shelley said, “and immediately spoke about the way squash was a vehicle for friendships around the globe.”

A plan was hatched. WISPA would organize an exhibition excursion with the best women. They would go to countries where squash was new and the world’s best would be newsworthy, show off the sport, catalyze development and get governmental attention. Tarantino’s only rule was that he would give the money to pay for the trip but do no work organizing it.

The first trip was a trial run: a weekend in Prague. A small fifteen-year-old boy came to the exhibition and hit with the women. Inspired by the visit, the boy, Jan Koukal, decided to follow his dreams. A year after the ambassadors visited, he turned pro. Koukal eventually reached world No.39 and won thirty-four PSA tournaments along with eighteen Czech national titles.

The tours now last a full week. Shelley makes the arrangements with the local squash federations (who pay for in-country transportation, meal and lodging for the tourists); Howard Harding, the longtime squash media director, works with local media to organize press conferences and meetings to publicize the tour. Shelley goes down the ranking list until he finds an available player. Spots on the tour are highly sought after: players don’t say no. The first thing Nicol David said after coming off court when she clinched the world No. 1 ranking was: “Now I can come on the tour.”

The tours are arduous. There is a lot of squash, sometimes six or seven hours a day. For Low Wee Wern, one day included five different matches. “The travel was exhausting,” said Rachael Grinham, who went on three tours. “As pros, we are used to going to one place and then not moving for a week, having days full of downtime. On the tour you are constantly on the go, traveling, talking, playing.” Sometimes, it is tough on the stomach. Fitz-Gerald got sick in Thailand in 2002, straight from her first meal; Natalie Grainger got food poisoning in El Salvador in 2000.

Very often, the effect has been subtle: the thousands of players who view the tour and meet PSA stars have translated into lifelong players; in turn these players sustain clubs, enter tournaments and help grow the game. It has a regional spillover: players, coaches and officials travel hundreds of miles, sometimes from neighboring countries, for the tour. (In Armenia, one of the keenest players was an architectural student from Iran named Pardis Mahmoudi; in Kiev, there were participants from Belarus and from cities across Ukraine, a country nearly the size of Texas.) After the tour, more courts are built and more governmental support flows into the squash federation.

“Every ounce of publicity is wrung,” said Howard Harding, the WSF media director. “We’ve got a good story: the world No. 1s in a new sport. The press conferences, the meetings, the exhibitions have an extraordinary effect. Local officials are stunned that the players are doing this for free. They can’t believe it that the world champions are giving their time and making this effort. For them they are the best days of their squash lives.”

Three times—in Iceland in 2007 and Vietnam and China in 2008—Shelley and Tarantino tried a different tack by parachuting in a fully-fledged WISPA tournament for a country that had never hosted a pro event before; these WISPA Premiere Series events in Reykjavik, Hanoi and Hangzhou functioned much like an ambassador tour.

Sometimes the growth is slow and incremental but steady. The 2018 World Masters, held in Charlottesville, had more than two dozen players from former ambassador countries including Argentina, Chile, Czech Republic, China, Italy, Malaysia, Namibia, Norway and Peru. Norway is an example: after the 2006 visit, many clubs built courts, including one with four all-glass courts; today Norway has thirty-six clubs registered with the Norwegian squash federation and since 2016, a national coach Lauren Selby.

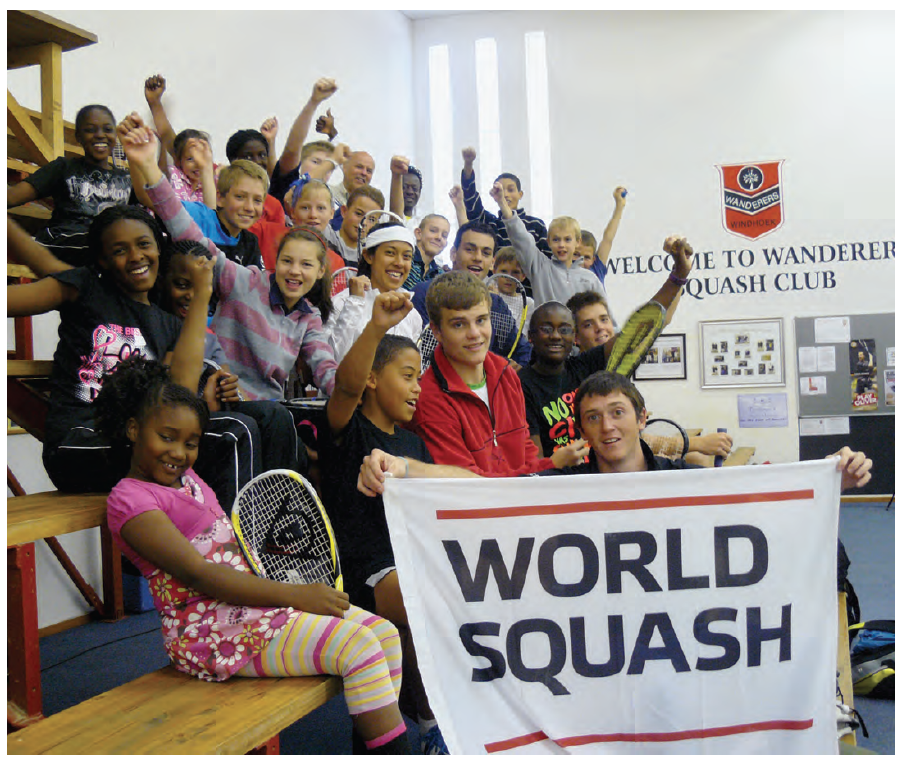

For some countries, the effect is almost immediately tangible. The visit to Peru in 2000 helped the national coach, Jose Manuel Elias, whose son Diego is now a top-ten player. After the visit to Namibia in 2012, Windhoek hosted the 2014 World Juniors, making Namibia just the third African country, after Egypt and South Africa, to host a world squash championship. The visit to China in 2005 was stunningly successful: the Chinese squash federation put up a glass court and the exhibitions were shown on all three national television stations. This directly led to the first pro squash tournament in the country, the China Open in 2008 in Shanghai and eventually the staging of the event along the iconic Bund; China has now hosted nineteen PSA events. More recently, the 2016 trip to China focused on the city of Dalian; last month Dalian hosted the first-ever world squash championship in China with the Women’s World Teams.

In 2010 Shelley left WISPA to become the executive director of the World Squash Federation (WSF). After a year’s hiatus, the tours resumed under the aegis of the WSF rather than WISPA. This meant a top male player joined the top female player, reducing the frequency of a common occurrence on the tour: a local male player whose ego would get bruised by losing to a woman. It happened almost every year. In Kenya in 2001, a Zambian man traveled to Nairobi to play Sarah Fitz-Gerald in an exhibition. “After I won the first game,” Fitz-Gerald said, “his behavior completely changed. He was blocking, charging, big swings and fist pumps after he won a point. It was unpleasant. I was fuming as it was supposed to be an exhibition. I got myself fired up and beat him in three. Afterwards, he came up and made a point of telling me that he had an injured thigh. Pfft—he just didn’t like being beaten by a female in front of a crowd.” The man came back the following day for a rematch and Fitz-Gerald again beat him.

With the restructuring the tours under the WSF, Shelley added two more people: a coach who hosts coaching workshops and a referee who leads seminars about officiating. Most often, Ronny Vlasseks, the Belgium coach, has served as the coaching leader and Marko Podgorsek, the Slovenian referee, has been the officiating leader.

Armenia and Ukraine in 2018 were archetypal examples of the tour’s two most common squash nations. The first squash courts in Armenia were built in 2011 by an industrialist who had picked up the game while working in Montreal. Today there are seven courts in the country. For a small sporting nation, it was big news to have world-class athletes like Ramy Ashour and Camille Serme in the country. Ukraine’s first courts, on the other hand, appeared in the mid-1990s and today there are about fifty nationwide. There, meetings with sports ministry officials were coupled with packed coaching and referee sessions and exhibitions that inspired the nascent squash community.

The tours are more than just squash. In Armenia, they took us to a fourth-century monastery carved out of a mountain, a beautifully situated Roman temple and the country’s moving genocide museum and memorial; in Ukraine, we visited the incredible 200-foot high Motherland statue commemorating the Second World War. Sabine Schoene carried a squash racquet up to Machu Picchu so she could hit a ball at the historic site. Vanessa Atkinson’s strongest memory from her 2003 tour to Russia was playing cards on the overnight train from St. Petersburg to Moscow. Mohamed ElShorbagy recalled a large, late dance party in Caracas. Linda Elriani loved hot-air ballooning in Kenya (she also went through fifteen rolls of film during her week there).

The 2006 tour included a visit to the world’s northernmost court, in Longyearbyen, on the Norwegian island of Svalbard, less than 600 miles from the North Pole. While on Svalbard, they were taken dog sledding. At one point coming down an incline, the sled hit a bump and Shelley tumbled off; Sarah Fitz-Gerald was left alone careening down the hill with no brakeman. Luckily the leader managed to halt the sled. A year later, they went to Las Hayas, a hotel in Ushuaia, Chile, the home of the world’s southernmost court. They also opened the national squash center in Kathmandu (and Tarantino paid for the center to get running water).

Like with all traveling, unexpected cross-cultural moments have been a delightful byproduct of the ambassador tour. Tarantino’s motto is “squash is not the reason, it’s the excuse.” There are hours of conversations, historical lessons writ large and small and surprising friendships. In 2018 learned about recent revolutions—Ukraine’s four years ago and Armenia’s this past spring. A few months after the 2003 tour to Russia, the National Hotel where they stayed in Moscow was blown up by a suicide bomber, killing five people. “These trips are intense, sometimes even spiritual,” Tarantino said.

Nicol David, a veteran of a record nine tours, was constantly recognized. Siyoli Waters remembered a group of Malaysians snapping photos of David near a cable car in Switzerland. Once, while the tour was in the dark of Gunung Mulu caves of Sarawak, a gaggle of visitors recognized her.

For Tarantino, the most memorable moment was in 2007. As they were getting on a plane heading to Montevideo, David was spotted by Nando Parrado. “I am Nando,” he said. “I can tell you are Nicol David.” Parrado was one of the rugby players on the Uruguayan plane that crashed in the Andes in 1972 (El Milagro de los Andes, immortalized in the book and movie Alive). When everyone landed in Montevideo, Parrado escorted them to the Old Christians Club, where the squash exhibition was being held that evening. Old Christians was also the club where the players on the 1972 plane were from.

In one simple gesture among the many created during all these years of travel, Parrado gave Tarantino an Old Christians tie—his favorite souvenir from all the tours.