By James Zug

When Gregory Gaultier won the 2015 Men’s World Squash Championships, the scene was perhaps as dramatic a moment as we have ever seen at the forty-year-old event. Gaultier was avenging nine years of agony.

The finals of the 2006 World Open, held in front of the Pyramids of Giza, was the original, irreducible source of the Frenchman’s pain. In the semis he had unexpectedly beaten hometown favorite and defending champion Amr Shabana (and expectedly Ramy Ashour in the quarters). Against David Palmer in the finals, he rushed out to a huge lead, taking the first two games 11-9, 11-9.

In his entire career up to then, Gaultier had never lost a match after a 2-0 lead.

He reached 9-7 in the third. Two points from victory. He then gave up four straight points, the last on a flukey back wall nick of Palmer’s. In the fourth, Gaultier again built leads of 5-0 and 8-2 and then got to 10-6: four match balls. He lost all four, including one on a Palmer mishit and another on a controversial (read: bad) referee decision.

Huge tension on the edge of Cairo, the roofless court, the thousands of breathless fans, the warm desert air, the stench of smothered adrenaline, the jinx of the Sphinx. Tiebreaker. Gaultier saved a game ball and then at 12-11 had a fifth match point. But he tinned a dropshot. He lost the game 16-14. He lost the fifth 11-2.

Some said afterwards that he had a penchant for choking in the big moments. Not true. His ratio in finals is pretty normal, upon inspection: according to SquashInfo.com, he’s made sixty-seven PSA tour finals and won thirty-two of them. Nick Matthew, by reputation very mentally tough, has reached sixty-eight and won thirty-three. (The best men’s ratio in modern times is Peter Nicol at sixty-nine and forty-nine.)

Gaultier’s record in World Championship finals, on the other hand, was not good. After the Disaster in the Desert, Gaultier reached three more finals and lost all three: in 2007 in Bermuda to Amr Shabana in three; in 2011 in Rotterdam to Nick Matthew in four; and in 2013 in Manchester to Matthew in five (Gaultier came back from 0-2 down, saved a match ball in the third but succumbed to cramps and exhaustion and like in Cairo lost the fifth game 11-2). After making his fifth final in Seattle, a month from turning thirty-three, he faced a record he didn’t want to see: Chris Dittmar went 0-5 in World Championship finals.

Observers tend to look back at junior results to see hints of future greatness or mental weakness. Our first view of the Frenchman was as a cocky fifteen year-old, at the 1998 World Juniors at Princeton. In a gust of teenage consanguinity, he and his two French teammates, Romain Tenant and Nicolas Siri, dyed their hair in the colors of the French flag. Gaultier drew red and for the fortnight patriotically sported a clown-like, brightly bleached mop of hair—Burgundy red, with notes of cherry if you want to recall the vintage.

Gaultier swept through three rounds that fortnight before Nick Matthew chopped in the round of sixteen 0, 3, 4. But he was still pegged as a rising star and potential top-ten professional. (Six months before Princeton, he had reached the finals of the U16 at the British Junior Open, beating wunderkind James Willstrop in the semis.) The following year he again faced Willstrop in Sheffield, this time in the finals of the BJO’s reconfigured U17 draw and memorably came back from a 0-2 deficit to slip past him 10-8 in the fifth. He reached the finals of the next World Juniors, in 2000 in Milan, where Karim Darwish dismissed him quickly in three. He finished out his junior career by beating Willstrop twice in European Junior Championship finals and once in the BJO U19 final.

Some even went further to locate the source of Gaultier’s losses. Squash had been his obsession since he was four years old. His father had died of cancer when Gaultier was three, and a year later his mother opened a four-court squash facility in Audincourt, in northeastern France. Gaultier was on court all the time as a youngster, impatient to win.

As an adult, Gaultier was known for angry outbursts at referees, for losing his concentration. He sped at one hard-charging, wheels-squealing velocity. He worked out relentlessly. In a sport filled with monastic devotion to training, Gaultier was ferocious. He trained harder than anyone else. His Achilles heel, in some ways, was his inability to ramp down his emotions on court. When frontrunning, he quick-served, rushing to get the ball after a winning shot. But any Gaullic sangfroid disappeared after a bad decision or a lucky shot by an opponent. “It’s hard to change Greg,” Renan Lavigne, his coach, was once quoted as saying. “It’s about changing his behavior towards referees. It worked in the beginning by telling him to focus his energy on the match. But unless you phone him 50 times a day, he will forget. It is frustrating as I know he can take it to another level, but he still has his old devils inside him.”

Late in his career, at an age when most players succumb to the ravages of time, to injuries, to a distaste for travel, to a need for a wider horizon than twenty-one by thirty-two box, Gaultier stabilized. In 2013 he married Veronika Koukal (highest world ranking: seventy-nine; and the sister of Czech star Jan Koukal) and they had a son Nolan. He moved to Prague, where the Koukals are from. He began to take a longer view. He began to see himself as a husband and father and not just a squash player. At the same time Renan Lavinge took over as French national coach, replacing Gaultier’s long-time mentor Andrew Delhoste, and assembled a fresh team around Gaultier.

After the World Championships in Seattle, I asked Gaultier what the secret was, how did he endure the wrenching defeat in Cairo, all the other losses in the final of the World Championship and come back? “There s no secret,” he said, issuing almost a definition for resilience. “Hard work, discipline, perseverance and the belief you can always do it. It wasn’t an easy task to forget all my losses over the years, but my career was far from finished, so as long as I kept playing I kept on setting goals for motivation. My losses were experiences and probably helped me to be more relaxed and to deal better with all the pressure. Instead of a negative approach, I changed and looked at the positives of the losses, to see what I did well and what I could change to play better in a final of a world open.”

Then he added the kicker: “I always believed in myself.”

The world’s richest-ever squash tournament, the $325,000 Men’s World Championships were in the United States for the first time. The host city was Seattle, which had ironically hosted the only other adult world championship ever held in the country, the 1999 Women’s World Open. Shabana Khan helped direct that championship, which was hosted at the Seattle Athletic Club. (Cassie Campion won the title, beating Michelle Martin in the finals) and was again at the fore this time around, along with her younger brother Murad.

The official home was actually not Seattle itself, but Bellevue, the suburban city on the outskirts of town (it took me exactly a half hour to come by city bus from downtown Seattle). The host club for the qualies and some of the first round was the Pro Sports Club, a 35,000-member, nine-court behemoth near Microsoft’s campus. Today it is the squash home of the Khan family, the Seattle dynasty headed by patriarch Yusuf Khan, and one wall near the courts boasts a colorful mural of the clan.

Pro Sports also has a small pro shop, which was helpful for Declan James. In the middle of the Englishman’s first-round match with Karim El Hammamy, James suffered a cut, which led to blood on his shorts. During his injury timeout, he grabbed his wallet out of his squash bag and shot up the stairs. A few minutes later he reappeared: he had dashed to the pro shop and bought a new pair of shorts, which he quickly donned. (To no avail, as he lost the two-hour five-gamer.)

Short malfunctions happened a few hours later at the events other venue, the Meydenbauer Center. Mazen Hesham’s shorts ripped just one minute before his first-rounder with defending champion Ramy Ashour. The twenty-one year-old, playing his idol for the first time ever, didn’t panic. He quickly borrowed Ali Farag’s Harvard shorts, which were however a bit too tight, and sent Tarek Momen hustling back to the hotel to fetch one of his own pairs. For the record, Hesham played better in the second and third games.

The Meydenbauer, Bellevue’s convention center, was a good choice of venue in some ways. Its 36,000 square-foot main hall boasted an enormously high ceiling. At the 1999 Women’s World Open, Shabana Khan had to take out the foam ceiling in the gym at the Seattle Athletic Club to squeeze in the portable glass court. “When I saw the Meydenbauer,” Shabana said, “I knew we could host it there.”

Pipe and drape ensured the room with the ASB GlassCourt felt intimate for the 800 spectators. Mark Alger, the 1981 national singles champion and Seattle townsmen, helped as a master of ceremonies, along with Britain’s Paul Walters. Both Jahangir Khan and Geoff Hunt, two former world champions, spent time at the Meydenbauer—for much of the tournament, Jahangir was found rooted next to his distant cousin Yusuf. Jahangir often spent his summers with Yusuf and his family during his playing career and seemed right at home with his relatives and autograph seekers orbiting around him.

Squash has always had some of the most accessible professionals in the world. The World Championships sponsors included Skype. Three hundred fans from around the world daily joined a live Skype group chat and players like Gaultier, Mohamed Elshorbagy and Miguel Angel Rodriguez sat in for live question-and-answer sessions in which fans were able to submit video messages. (My favorite was Gaultier answering a question about how to grip the racquet.) After the final, Gaultier got on a laptop on the glass court to share the excitement of his victory on Skype. “I barely slept last night,” he admitted. “Squash is my life.”

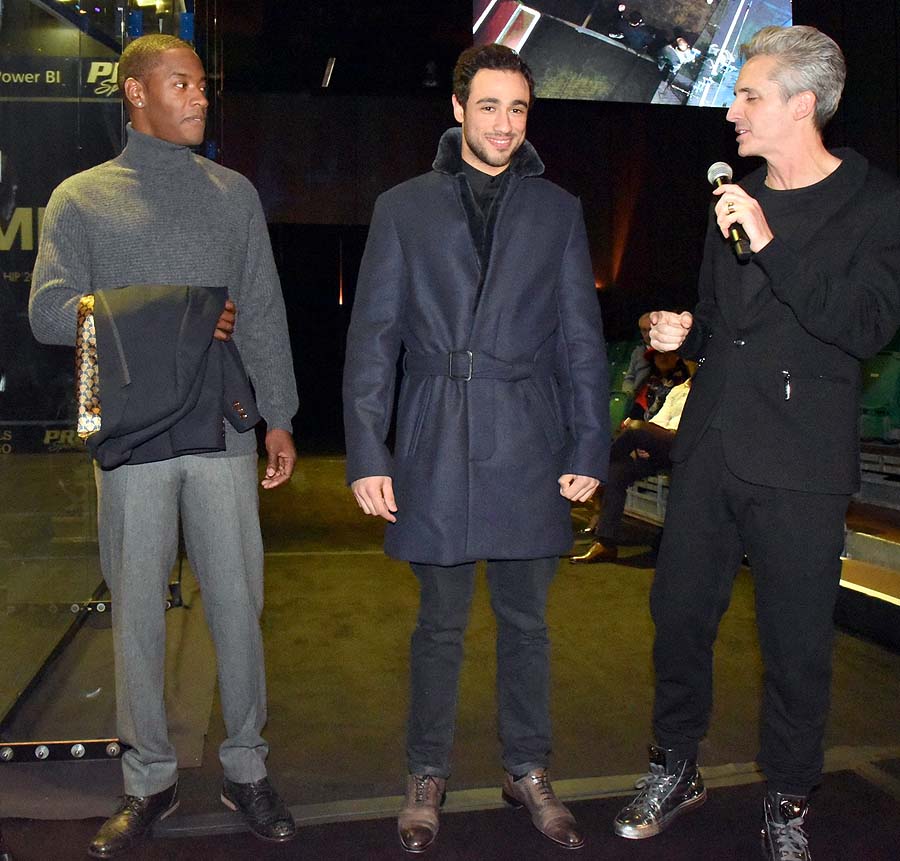

This year’s tournament had an unusual twist: fashion. A Neiman Marcus trunk show punctuated the quarters and a David Lawrence fashion show preceded the semis. David Lawrence was a former sponsor of Shabana Khan’s. Eighteen models exhibited seventy-two different outfits on a runway outside the court. Ramy Ashour even sported a couple of leather overcoats.

Americans are still not fashionable in the Men’s World Championship. Ten Americans, including Mark Talbott’s son Nick and two of Yusuf Khan’s grandsons, started in the qualies but only Todd Harrity made it through to the main draw. There he pulled off the upset of his young career, toppling Alan Clyne in five. It was the first main-draw win for an American male at the World Championships since Julian Illingworth in Kuwait in 2009 and only the third in history. (Illingworth, easing into retirement, came up from Portland as the event’s wild card and lost in three to Miguel Rodriguez.) Harrity lost in three in the next round, courtesy of Mathieu Castagnet, but his performance bodes well for the future.

Upsets were surprisingly common. Unusually for a sixty-four player tournament, four of the first-round matches and three of the second-round matches went the distance. Ali Farag, in his first world championship, reached the quarters. (It was the best world championship debut since Mohamed Elshorbagy’s bow at the 2008 world championships when he also reached the quarters.) Farag still wears his Harvard kit. He told me he does it because he’s proud of having played for the Crimson. It is also a sign that he doesn’t have a clothing endorsement.

James Willstrop ran rampant in Seattle. Back after a long layoff due to injury, Willstrop topped Elshorbagy, a finalist in 2012 and 2014 and this year’s number-one seed Then he vanquished Rodriguez to reach the semis. Karim Ali Fathi knocked out eleventh-seed Peter Barker in the opening round. “I was intimidated playing Barker,” Fathi said afterwards. “He’s such a great player, he got to five in the world.” Such is the strength of a world ranking number in the minds of other players; Barker announced his retirement a few days later. Fathi bested Fares Dessouki in the second round before running into the Gaultier guillotine.

That second-round match was typical of the action in Seattle: Egyptians contested seven of the sixty-three matches between themselves. It happened so much that Amr Shabana, the designated court-side counselor in between games, joked about ordering room service and watching from the hotel because he kept on having to recuse himself.

When not walking the runway, Ramy Ashour played four of those seven intra-Egyptian derbies. The verdict on his balky hamstring came during the second point of the fifth game of his quarterfinal match against Omar Mosaad. At some moment during the frenetic rally (he hit the ball off the back wall and then had to deeply lunge for a ball in the front right corner), he twinged the hammy again. Ashour won the next four points but you could see he wasn’t moving properly and then he all but gave away the next ten points and the match. After last year’s miraculous return from injury after a long layoff, it was too much to hope he could do it two World Championships in a row.

Early on it looked extremely unlikely that Gaultier would have another chance in a World Championship final. He arrived in the Northwest with a cold and it got worse in the damp, rainy Seattle weather that dominated the first half of the event. “My throat was inflamed,” he told me. “My lungs, nose and throat were blocked. I struggled to breathe properly.” He lost his voice and his inimitable Gaullic accent—diphthong-less, schwas-stuffed—was a whisper. He went to an acupuncturist the day before his quarterfinal match with Farag. “I really felt good the next day and then the long match with Farag helped me to open my lungs.”

When Gaultier wins a match, he often immediately melts. It is as if he’s shot out of his little eddy of stress and suddenly swimming—drowning—in a river of relief. After the handshake, he hugs opponents, he whispers long soliloquies into their ears, he taps them on the shoulders, he holds on to them. The dance is done and he won’t turn off the music.

In Seattle, he knelt to hug a collapsed, cramping Farag and then literally helped him off the court. The end of the finals was surreal. Gaultier was up 2-0 and 7-4 in the third, again tantalizingly close. Again a lead slipped away as Omar Mosaad came back. But down 8-10, Gaultier fearlessly babied two straight balls into the nick to level the game. Two points away. At 10-10, Gaultier broke his strings on a low hard backhand winning rail, his signature stroke.

So 11-10. One point away, again. A sixth world championship point, his first in over nine years, Gaultier had to exit the court and get a new racquet. Over forty seconds elapsed. Enough time to freeze with panic or flow with calm. It was like an opposing coach calling a time-out on a game-winning field goal in order to ice the kicker.

It mercifully ended quickly, a short rally, an ungettable straight drop. Gaultier screamed. He looked to Mosaad. He put his hands on his head, as if waking from a dream. He then hugged Mosaad. He hugged again. Mosaad tried to move on, one arm still loose, holding his racquet, and exit the court, but Gaultier, emotion pell-melling out of him, clutched at Mosaad and spoke and spoke and would not let him go.

Finally, Mosaad left the embrace and the new world champion burst into tears.

It was the 602nd match that Gregory Gaultier had won on the PSA tour and it was the sweetest.