By Richard Millman, Owner – The Squash Doctor Corporation

For reasons that are not always immediately clear, we of the Squash playing community seem to lose all sense of reason when finding ourselves with an opportunity to play at the ‘Front of the court.’

As I have mentioned on numerous occasions and as many of you have clearly espoused, the primary responsibility of a human being and, accordingly, of a Squash player, is to live or survive.

This activity in and of itself is demonstrative of success, since those that have not succeeded are no longer here to talk about it.

Of course there are varying degrees of success, but at the base level success in life or in Squash means surviving.

Why then do many of us allow a rush of blood to the head to tempt us towards suicidal behavior when we find ourselves in the hallowed ground of: ‘The Front of the Court!’

First and foremost we have to understand the reasons why to play to the front.

Squash is a logical game but that logic needs to be considered in light of equilateral conditions, otherwise it is easy to believe that illogical behavior can be considered practicable.

It may be that you have gotten away with certain behaviors when competing against opponents who were unable to deal with your strategy—however that is no guarantee that you will be successful with such stratagems against players who are as (or more) capable than yourself.

Here are some phrases that have tempted many a player into mental cul de sac from which they have taken a long time (maybe even a Squash career) to extract themselves:

I am going to hit a kill shot

I was going for a winner

I wanted to finish the rally.

If you have found yourself using or tempted to use some version of one of these, cease and desist henceforth.

If your primary responsibility is to survive, your first focus must be always to ensure that you will be in position to deal with any possible response from your opponent.

How are you going to do that if you have predetermined that your opponent is not going to get your shot back?

Answer: You won’t.

Once you think about ending a rally, the first thing that stops is any planning of future activity. Hence, if by some miracle your amazing winning shot is returned, you are completely impotent.

On the other hand, if you always expect your opponent to return your shots, this frees your hand to aggressively attack with the express purpose of hurting your opponent rather than finishing them.

The net result is that prior to executing your attacking shot into the front, you will have already positioned yourself advantageously to cope with your opponent’s retrieval of your attack.

This actually produces a completely different mechanical/technical stroke execution and ensures that you utilize your leg muscles to execute your attack—because you need to be mobile as you hit your attacking shot to cover all possible returns. If you design a shot to finish a rally, you tend to become static and your lower body is deactivated (after all, why move if your opponent isn’t going to get your shot back?) and therein the upper body takes on the responsibility of both accuracy and power, becoming tense in the process and losing precision. In addition, with the legs becoming static they no longer operate to evenly control balance and you tend to fall over when you go for your ‘winning’ shot.

So not only is the concept of ‘a winner’ a bad theory, it produces poor technique and far higher error rates.

Why play to the front? To attack and ramp up pressure, fully expecting the opponent to return your shot but hopefully to be weakened in some as yet unclear manner, and hopefully to lead to a beneficial product at some as yet unknown point in the future.

Of course if it turns out that the unknown point is immediate, great! Just don’t count on it—or your whole system will break down.

There is another reason to play to the front also. That is when you are on the receiving end of an attack.

Every piece of behavior in Squash takes time and how you behave needs to be cognizant of the availability of time—just so when someone has attacked you at the front. It might be your preference to play a high ball to the back to escape this attack and put yourself back in charge of the rally. However, sometimes even this sensible defensive move just takes too much time in comparison to what you have available. In these circumstances you may have to use the minimal time technique of a defensive ball to the front—because that is all you have time for.

So the when of the front court game may be both offensive and defensive.

Offensively it is never enough to play to the front because you have a loose ball at the front. Playing to the front has to be based not only on the position of the ball but also of your opponent and of yourself.

If it is relatively early in the rally you must ask yourself several questions:

Is my opponent out of position? Am I in position? Even if my opponent is out of position, how fast/fit is he? If my opponent gets to this front court shot, how easily can I defend a counter attack from him. How confident am I in my short game (accuracy etc)? Am I applying the most fundamental principle of the game—namely, will this shot leave me in position to survive or will I be risking my own survival by being tempted by the possibility of killing my opponent?

Defensively, many of these questions may be taken out of your hands. And that may be a good thing — if you feel threatened you will be much more likely to play to improve your own situation rather than to worsen that of your opponent.

And therein lies an interesting truth— namely, that human beings are better at hanging on to life than they are at killing it off.

So when you attack, it would behoove you to attack with the sort of energy, concern and sincerity that you might use to survive—assuming that life is important to you.

The front court game, therefore, has two types of motivation—attack and defense. This is the what of the front court. If you aren’t attempting one of these with real focus, you shouldn’t be playing to the front. It isn’t a place to aimlessly pootle about.

In this vein what to play and how to play ‘front court’ shots are closely related. Every situation that arises requires careful contemplation before the precise ‘fingerprinting’ of the exact way in which the shot needs to be executed can be decided.

Variables such as: where is the opponent, where am I, how tight is the ball, how soon did I arrive, how adept am I at certain techniques, what is my capacity to defend/retrieve a possible counter attack—must be first determined before the shot can be molded.

And of course these variables need to be ‘felt’ rather than ‘thought’ (i.e., this has to be a product of the sub-conscious automatic mind and not the sluggish conscious deductive mind).

The only way to perfect the skilled determination of what/how to play in the front court is by massive repeated exposure until the laborious process of consciously determining these details becomes ‘second nature.’

When to play short is also a close cousin of why, what and how.

When, however, can materially change the base reasoning of why, what and how.

Situations arising in the first game against a fit and confident opponent are frequently inappropriate where later in the match they will be extremely appropriate.

It is essential to monitor the condition of your opponent’s capacity to deal with certain shots and to make every attempt to ‘investigate’ and limit their capacity before fully committing to a ‘Front court’ attack.

Making the opponent go to the back corners half a dozen or more times before finally attempting to hurt them in the front corner is always a wise move against an experienced and capable opponent.

And always assume that your opponent will definitely retrieve your attack—no matter how thoughtfully you have executed it. Your focus must be to hurt your opponent—never to beat, kill or finish your opponent. You cannot predict the opponent’s ability or inability to retrieve your ball, and unless you keep your guard up, you can easily become the victim of complacency.

So when is a matter of determining the moment that your front court attack is appropriate and of understanding the various factors that make the moment opportune.

Finally who and when are closely related in that playing to the Front Court is largely dependent upon the relative capacity of your opponent to play under those circumstances.

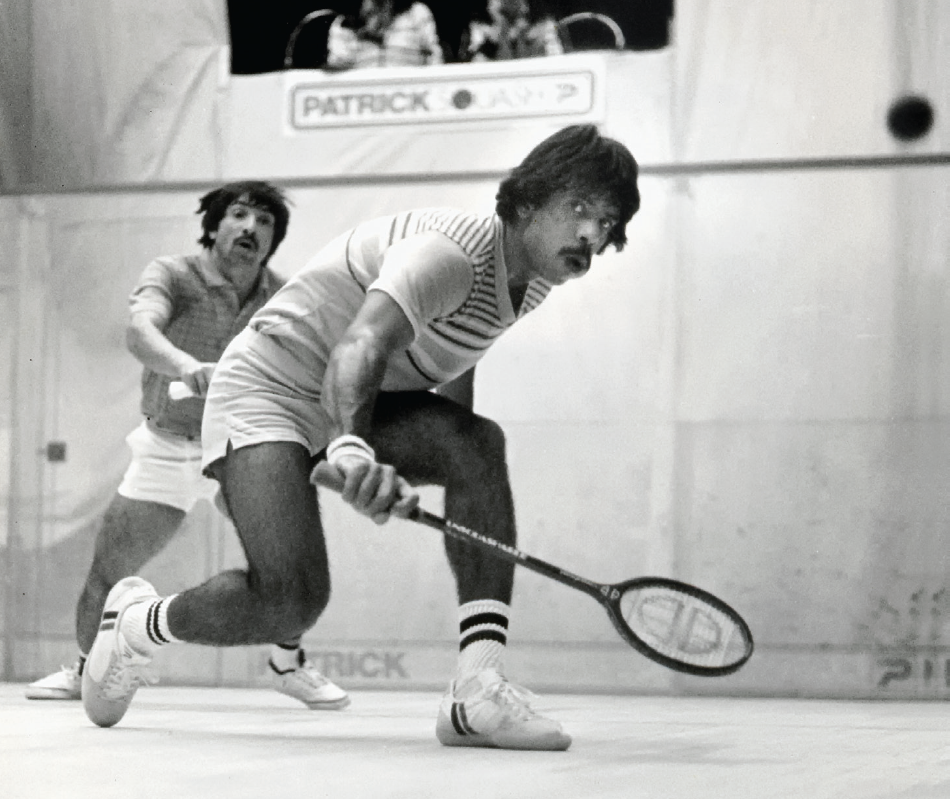

I have a wonderful memory of two great English players: David Thomas and Zain Saleh.

With great respect to these two extraordinary exponents of our Sport, neither of them were very adept at attacking to the front of the court—relative to their overall abilities. However, both of them were in the highest one or two percentiles in terms of their ability to retrieve.

Imagine then the spectacle of these two giants of the game duelling with each other—neither able to execute a well-conceived front court attack and, even if they could have done so, both of them were very nearly superhuman in their ability to retrieve seemingly impossible balls.

As you can imagine, the titanic battle that ensued was both spectacular and comical as the two players continuously embroiled themselves in difficulty by attempting poor front court attacks only to then heroically rescue the situation.

Here then are the Five wise men of the Front court game.

Listen carefully to their words and you may become an aficionado of this particular area of the court that has been an unnecessary pitfall for so many.