By Richard Eaton

Photos by Steve Line/squashpics.com

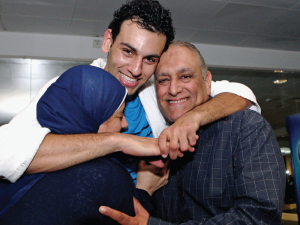

Ramy Ashour’s recapture of the world title amidst the soaring city of Doha completed a shift in power at the top of the game and highlighted a pilgrimage of rescue for the sport’s most entertaining player.

A few years ago Doha was little more than a small town on the edge of an Arabian desert. And a short time ago Ashour was a player stuck in an injury-blighted mire of distressing under-achievement.

Now the Qatari capital, launching its Islamic architecture skywards through the wealth of its oil and natural gas, sits with Shanghai and Dubai among the world’s most rapidly upward-growing cities.

And it was here that Ashour proved himself the best and the most entertaining player in the world, with dynamic dismissals of Nick Matthew, the defending champion, and Greg Gaultier, a former World No. 1, and heart-in-mouth survivals against Omar Mosaad and Mohammed El Shorbagy, his compatriots.

It was the ideal location for the Egyptian to deliver such scenery-shifting performances. For without his visits to Doha earlier in the year the former world champion would never have achieved what he called “my greatest moment.”

Ashour had collapsed in pain and tears at the previous two World Opens, in Al Khobar and Rotterdam. His explosively unorthodox style, unpredictably staccato court coverage, and naive responses to ensuing injuries were a lethal cocktail that became career threatening.

“I could have given up at any second,” Ashour said of his mood early in 2012 before making desperate three-hour flights from his Cairo home to Doha’s sports academy, Aspire, possessor of the most modern sports science facilities in the Middle East.

“Instead it’s all been saved for me,” he added, with a hint of disbelief. Just as remarkable is that Egypt, the strongest squash nation, nowhere had the expertise to preserve one of the greatest talents it has had.

Egypt, in the form of Ashour and runner-up Shorbagy, has superseded England, in the form of Matthew and James Willstrop, at the pinnacle of the game, but with few of the medical, physiological, and psychological resources available to their rivals.

Egypt, in the form of Ashour and runner-up Shorbagy, has superseded England, in the form of Matthew and James Willstrop, at the pinnacle of the game, but with few of the medical, physiological, and psychological resources available to their rivals.

“I thought I was a dedicated player and I was nowhere,” Ashour said. “Before I was doing things randomly. Now I have more awareness. It’s been one of the biggest changes of my career.

“They (physiologists at Aspire) told me I had to stop for three months and do nothing, which I found one of the hardest things to do. Then I started learning. I was given a regime which helps me to sleep right, eat right, and live right. I enjoy it and it’s had a big effect.

“I could have given up at any moment, and now I have a way of doing things which has changed my life.”

Those who wonder if these dramatic words emanate from his liking for colorful language, should know Ashour’s whereabouts during his absence from the PSA World Series finals in London in January. In Doha, at Aspire.

While there he may have reflected again on the curiously fluctuating final which he won 2-11, 11-6, 11-5, 9-11, 11-8 against Shorbagy, a match that brought a shift in age groups as well as across continents.

While there he may have reflected again on the curiously fluctuating final which he won 2-11, 11-6, 11-5, 9-11, 11-8 against Shorbagy, a match that brought a shift in age groups as well as across continents.

That is because the semifinals saw the 25-year-old Ashour beat the two-time world champion Matthew by 11-9, 11-6, 9-11, 11-8, while the 21-year-old Shorbagy got past the top-seeded Willstrop by 11-9, 9-11, 14-12, 4-11, 11-8.

It required Ashour to overcome a conduct warning for barging as well as complaints from a bravely determined Matthew, and Shorbagy to survive cramping hamstrings, a 3-6 final game deficit, and 112 minutes of toiling rallies against the other Yorkshireman.

No-one should dismiss the capacity of these resilient, late-developing Englishmen to win big matches on occasions, but it now seems less likely that either Matthew, aged 32, or Willstrop, 29, will exert long-term influence on the game.

Ashour was as passionate about the state of his country as he had been about proving he is again the best player. Several times he claimed to have joined demonstrations in Tahrir Square, later tweeting his support of them.

“This is how the true real moderate Egyptians unite and stand up for themselves,” he wrote, displaying quotes and images from people in front of the Presidential palace.

Ashour also hoped that winning the world title might offer just a mite of morale boost for protesters. “I love my country but we are struggling at the moment,” he said. “I feel for the less fortunate people, as the revolution was basically raised to help them. But now they are the ones suffering the most.”

He was more confident about his own future than his country’s. “I feel there is a lot more to come,” he said, celebrating Aspire’s transformative influence on him. Shorbagy sounded even more confident about what lay ahead.

“I am a decade younger than most of the leading players,” he said, referring not just to Matthew and Willstrop, but also Karim Darwish, a former World No. 1 from Egypt, who is 31, and Gaultier from France, who is 30.

“I can play my game and develop in my own way and my own time, knowing that in a while I will be playing against players of my own age group, all of whom I have beaten.”

It triggered eulogies from Egyptian head coach Amir Wagih, who had already overseen a sequence in which his country became the first ever to hold all four world team titles, men’s and women’s, senior and junior. “Our players have made good progress, but the future for some of them is looking even better,” he claimed.

“We have younger players good enough to make it all the way to the top,” Wagih reckoned, referring to Karim Abdel Gawad, the conqueror of the 12th-seeded Englishman Tom Richards in the first round, to Tarek Momen, who produced a sensational win over Matthew on the same court at last year’s Qatar Classic but lost to him this time in the last 16, and to the younger Shorbagy brother, Marwan, the world junior champion.

But all is not as well as this suggests. Funding has been substantially reduced following the ousting of President Hosni Mubarak, a squash enthusiast, and amidst the continuing political turmoil. Despite his optimistic words Wagih is moving to work in the United States.

Ashour’s optimism, however, is based on the present. His mixture of discipline and imagination against an in-form Matthew was perhaps his most significant performance, and his adaptability during a 12-10, 10-12, 11-6, 9-11, 11-3 quarterfinal win over Gaultier was, in the last three games at least, the most brilliant.

But Ashour’s 11-13, 12-10, 11-2, 14-12 struggle against Mosaad in the last 16 revealed vulnerabilities against a burly dominating presence and intimidating hitting. For 40 fraught minutes it looked as if he might be yo-yoing to defeat. Only after saving game points in the second and fourth games—preventing a two-game deficit and then avoiding a decider—did he wriggle through.

Afterwards came moments of crazy comedy from Ashour as he skipped the on-court chat with the master of ceremonies and post-match interviews with journalists, rushing off to a distant room, and hiding away to ponder his scare.

Eventually one journalist inserted his head horizontally around the door, and Ashour compulsively blurted some words, re-appearing rather humbly in the media room later on to ask what it was that he might have said.

“I was talking too much yesterday, and it got in my head,” Ashour concluded. “I was talking as if it was the end of the tournament, and I shouldn’t have done this.”

It indicated, despite his number four seeding, an awareness of being the unofficial favorite. After he had eventually justified that status by capturing the title, his emotional investment in it was articulated.

It indicated, despite his number four seeding, an awareness of being the unofficial favorite. After he had eventually justified that status by capturing the title, his emotional investment in it was articulated.

“To win the world title the first time was amazing,” he said of the success at Manchester, England, in 2008. “But when you win it (again) after a lot of struggle, it means something different, and it feels a lot different. I am proud of myself because I have been through many hard times. I feel like I am a stronger person now.”

In the final he had needed to be. Shorbagy moved freely despite his marathon with Willstrop the previous day, mixed the short and the long games well, and was remarkably calm.

Ashour was not. He started slowly, became unaccountably less inventive in the fourth game, and slipped in and out of his best focus during an up-and-down decider during which he trailed 7-8.

When it really mattered, though, he created four sharp forays at the front that snatched him the victory, and reminded us that he felt, in Doha most of all, that this was his destiny.

“I wasn’t as relaxed as he was. But at the end I tried to relax a little bit more,” Ashour said. His thoughts had been jumbling around “like a washing machine,” he admitted. “You have to stop them, and that’s the hardest thing to do in a world final,” he said.

Few know more about emotions like that than his friend Amr Shabana, the four-times former world champion whose quarterfinal exit, at the age of 33, had seemed ominous.

The great Egyptian disappointed himself in a 11-5, 9-11, 11-5, 11-4 loss to Matthew, who produced a tactically masterful display, delivering his increases in pace at cleverly timed moments.

Matthew might have won anyway, but it transpired that Shabana had not fully recovered from bruised ribs from a fall in Hong Kong a few days earlier. Frustration at the outcome caused him to avoid postmortems and plunge from the arena as though the sky had fallen in.

It was easy to imagine this might be his final curtain. Instead three weeks later Shabana avenged himself on Matthew while winning the World Series finals in London, and made it clear he would continue.

“A while ago I sat down and reflected on the big decision,” Shabana said. “I said I really don’t feel it’s the right time. I still feel I can be as good as anyone. It’s just that mentally sometimes I have had enough, especially after competing 18 years.”

Hence the 21st century’s most successful player will bring his wife and three children to his new domicile in Toronto, and use this and New York, another recent base, as well as his home city of Cairo, as stop-overs for a carefully rationalized schedule throughout 2013.

Matthew called Shabana “still a class act” and paid generous tribute to Ashour too after losing to him, volunteering that his imminent successor had been the world’s best player for some time. However, he also expressed loud disapproval at Ashour running into him and knocking him over.

It was one of several matches that brought refereeing issues to the fore. “That’s the fifth or sixth time it’s happened,” Matthew lectured the official. “I wonder if the roles had been reversed how long it would have taken to award a point.” His remark hushed a crowd which had noisily been supporting Ashour.

Willstrop’s win over Borja Golan was more mundanely controversial, the Spaniard repeatedly claiming he was unable to find a way round the Englishman. There were 57 refereeing decisions in only three games.

Nevertheless there were improvements in the video review system. The previous world championships final in Rotterdam brought decisions from a fourth referee that appeared to have been made on different bases from those made by the other three. This time there was better consistency.

There was also a dramatically effective intervention by Australian referee Damien Green during Ashour’s 12-10, 10- 12, 11-6, 9-11, 11-3 win over Gaultier. The first two games were edgy, patchy, and contentious, but the contest changed dramatically after Green stopped the match, stared at them both, and barked: “Everyone is here to see the best two squash players in the world—not two blockers!”

Thereafter it evolved into such an incredible contest, so full of sensational rallies and startling athleticism, that at the end the crowd stood to applaud.