By James Zug

Photos by Dick Druckman

Upon clinching a 11-6, 11-6, 11-4 win in his match against Yale, Baset Chaudhry stooped down and for three or four seconds yelled at Kenny Chan. He then left the court, without shaking Chan’s hand, and hugged some teammates and his parents. It was the clinching fifth match in the finals of the nationals. The senior co-captain had just secured Trinity’s twelfth straight national title and 224th consecutive win.

Seeing Chan exiting the court behind him, Chaudhry turned and bumped him back into the court. Immediately, his teammates and supporters, led by Simba Muhwati, a 2009 graduate, jumped in between him and Chan. The celebration moved away from the court’s door and Chan soon exited.

The whole incident lasted about fifteen seconds, including the elapsed time of hugging and celebrating.It ruined Chaudhry’s life.

Baset Ashfaq Chaudhry was the most celebrated recruit in the history of American intercollegiate squash.

Chaudhry grew up in Lahore. His father is a merchant: he has imported chemicals for the textile industry and now runs plastic factories. Chaudhry played squash at the Punjab Sports Complex. When he was eighteen, Chaudhry won the 2003 Asian junior championships and then played No. 4 on the Pakistani boys team that won the 2004 world junior team championship. In January 2005 he captured the British Junior Open to claim the Drysdale Cup, squash’s oldest junior title. He finished high school just before the British Junior Open triumph, and upon his return to Pakistan he started playing the pro tour. For a year and a half he had a go, traveling to India, Malaysia and Egypt for tournaments. He was taking university-level courses and living at home. In June 2006 he was ranked sixty-first in the world.

No Drysdale Cup winner had ever played American collegiate squash, except Anil Nayar at Harvard in the 1960s. (Marcus Cowie, the Trinity star of the 1990s, had been up 2-1 in the finals against Ahmed Faizy in 1996 before losing in five.) Chaudhry was considered beyond American collegiate squash—too talented, too old (he is now twenty-four) and, frankly, too Pakistani (not a single top Pakistani had ever played college squash in America, even before 9/11). But he was tiring of the tour. One incident stuck in his craw. He was in Cairo trying to get a taxi at rush hour with Amr Shabana. No one knew him in the streets. Here Shabana was, the greatest Egyptian squash player in three generations and yet he couldn’t catch a cab.

The team aspect of intercollegiate squash is almost always foreign to the overseas players when they arrive at college campuses. But Chaudhry had an instinctive appreciation of what was important at Trinity—the team. The first time he came to Paul Assaiante’s office, when he flew in from Pakistan, the telephone rang. It was his father. They talked for a couple of minutes in Urdu, a labyrinth of consonants and glottal stops. As Chaudhry stood at Assaiante’s desk, he saw a bowl in which lay the Trinity national championship rings. While he talked, he mindlessly fiddled with the shiny baubles: the gold, diamonds, the slogans (“Too Strong” “Never Fear, Never Retreat” emblazoned in diamonds), the finger-dropping weight.

Then he stopped, and put his hand on the phone’s mouthpiece.

“What are these, coach?” he asked.

“Those are the eight national championship rings,” Assaiante replied. “We make one after winning the national team title.”

“Order four more.”

He had a long transition to collegiate life. He was a practicing Muslim and had gone to Friday prayers and ate halal, so it took a while for him to find out how his beliefs meshed with living on an American college campus. On court, he was clearly a fantastic player, but his confidence slowly seeped away. He lost in a qualifying match at the 2006 U.S. Open in Boston to Tom Richards, a player he had always beaten before. After that he never played in another PSA tournament again.

He started losing challenge matches. After reaching No. 1 on the Trinity ladder, he lost in quick succession to Shaun Johnstone at No. 2 and Gustave Detter at No. 3. The best recruit in history and he’s playing No. 3? He managed beat the No. 4 player, Supreet Singh, and a month later had challenged back to the No. 1 spot.

It wasn’t until the finals of the 2007 nationals against Princeton that he showed his true form. He lost the first game to Maurico Sanchez 9-4. Sanchez had gone undefeated all year. All of a sudden Chaudhry rolled the next three games, 9-2, 9-2, 9-1. He was playing pro squash rather than college squash. He kept his drives super-air-lock tight, no matter how much duress Sanchez put him under and detonated the ball with unprecedented velocity. It was little noted in Trinity’s dual-match victory, but his match with Sanchez was a seminal moment in Chaudhry’s ascendance.

A week later, he fell in the semis of the intercollegiates. He played well in the morning, dispatching a pugnacious Kimlee Wong in the quarters. But that Saturday night in the semis against Siddharth Suchde of Harvard, he was out of sorts. In the middle of the first game, Sid coughed up a loose ball. Chaudhry stepped up and crushed it. Sid asked for a let. He got it. All of a sudden, Chaudhry was confused. It was not a let, at least in the way that international players would have expected. He did not take it in stride. He had to make an adjustment—it was like a pitcher learning to adapt to an umpire’s strike zone—and it rattled him. Sid took over, winning convincingly 9-7, 9-5, 9-6 and taking the title the next day over Sanchez.

His sophomore year, he was a different guy, more mature and settled. Moreover, he figured out college squash, that he would be pushed and battered and hacked, that although he cleared well, he would be accused—because of his size—of clogging the lanes. He became used to lesser skilled players getting physical with him.

He spent his summer back in Pakistan eating his mother’s food and training and came back to campus having lost twenty pounds. For a guy who was 6’5”, this was enormously encouraging, as he needed all the help he could get in accelerating around the court. He seemed stronger mentally too. His country was falling apart. He called home every day, even if he couldn’t afford it. Benazir Bhutto was assassinated a couple of blocks from his house. Yet, he seemed tougher with an inner maturity. He was always the gentle giant type, but now he was spreading beyond his roots. He started to see himself staying in the States after graduation. He began to eat non-halal meat and stopped going to Friday prayers. His studies were on track: he was majoring in economics. He trained ferociously.

He went undefeated. In the dual match against Princeton, Chaudhry faced Maurico again and destroyed him in three, 9-2, 9-2, 9-0. It was the most lopsided win I have ever seen at a No. 1 match between the two top-ranked teams in the country. Those guys had enormous egos to go with their talent and they simply never let a match deteriorate that completely. At the nationals, Chaudhry beat him 3-1. Down at Annapolis for the intercollegiates, he beat Gustav Detter in an anticlimactic final.

As a junior, Chaudhry steamrolled the rest of the country, except for Maurico, with whom he endured three titanic matches, battles a la Frazier v. Ali. In the dual match, he lost 9-7, 9-5, 6-9, 9-10, 9-2. It was a good match, but Maurico was just the better, more forceful player. Trinity won the dual match 5-4, but it was 5-3 going into the final game of the Chaudhry v. Sanchez match, so there was less tension in the fifth.

Eight days later Trinity and Princeton were in a terrific, six-hour showdown, perhaps the greatest collegiate squash match in history. In two matches, Princeton came within a couple of points of clinching a fifth win and the dual-match victory. It went to 4-4. Then Sanchez, down 2-1, went up 5-0 in the fourth. Chaudhry bounced back to 5-2 and then Sanchez stepped on the pedal and cruised to 9-2 in an eleven-minute game. In the fifth, he dashed to a 5-0 lead again. Chaudhry had lost nine points in a row and had just scored two in the face of Sanchez’s fourteen. It was a meltdown of epic proportions.

There is some disagreement over whether Chaudhry knew that the dual-match was at 4-4. Both Paul Assaiante, head coach, and his assistant James Montano recall telling him after the fourth game that they needed him to win. Chaudhry tells me that he misheard them and thought Trinity had already clinched at 5-3 and that only at the awards ceremony did he learn that it had been 4-4. When he won his match at the nationals his freshman year, everyone stormed the court (Trinity had won 9-0), so he thought the wild celebration was the same. “I honestly thought it was the same,” he says. “I thought, ‘It’s Maurico’s last game, his senior year and I don’t want to be beaten twice on his home court.’”

Either way, he made one of the most storied comebacks in college squash history. Down 0-5 in the fifth, he won three points in eighty seconds, then four more. The match got becalmed at 7-5, with errors, lets and more lets. Serving, Chaudhry smacked a rail that clung to the wall. At match point, he hit only crosscourts and passed Sanchez on a well-placed volley.

A week later he took his second straight intercollegiate title. Again, it was Maurico Sanchez in the finals. Again, it went to five games: 9-6, 9-10, 9-4, 5-9, 9-3.

This past season, he went undefeated, taking his career record to 55-2, which is pretty good for a #1 player. His toughest match was against Princeton’s freshman, Todd Harrity, in the dual match: 4-11, 11-9, 4-11, 11-7, 11-9. When he faced Harrity a week later, he put him away with a whoompingly brutal three games.

With the team winning the nationals at Yale, Chaudhry was headed towards a seventh national collegiate title, which only one other person has ever reached. In discussing the best collegiate player ever, you must ask how many titles did he or she win. Did he play #1 on the #1 team—a target on the target of everyone else? Did he lead? Did he come through in the clutch?

To many observers, Kenton Jernigan is the greatest of all time Yes, Jernigan went 42-0 in dual matches, which is the best percentage ever for a guy playing #1 all four years. But his Harvard teams were so much better than everyone else (the closest dual match they had was 7-2) that the pressure was not nearly as fierce as it was for Trinity: in Chaudhry’s career he led them through three 5-4 nailbiters, including the famous one he saved last February.

This made it all the more tragic when he came off the court at Payne Whitney.

Chaudhry is unfailingly polite. He has a luminescent smile. The first time he meets any adult, he called them “Mr.” or “Mrs.” When he was introduced to Preston Quick, who graduated from Trinity just ten years ago, he said, “Nice to meet you, Mr. Quick.” He is a heroic sleeper and can rack over a dozen hours at a clip. He loves ice cream. He’ll have it on pancakes for breakfast. He is forgetful. He loses his sweats. He loses his glasses (he wears contacts on the court).

He is definitely not the most talented player on the Trinity team. He was not gifted with great genetics. He’s just too tall and too big. He has had injuries: as a freshman he had shin splints and then a week before the team nationals sprained his right ankle and wore a boot all week. He hurt his wrist a year later. He also endured a socially difficult disease. It was an unusual skin condition called non-segmental vitiligo. A few years ago parts of his knees, hands and eyes started to lose their pigmentation. The pale pink patches spread so that both his kneecaps were almost complete pink and his eyesockets gave him a slightly raccoon-ish look. His father has it too.

He is the hardest worker on a squad bursting with training addicts. He practices for hours. He is a co-captain, along with Supreet Singh, and talks every morning on the telephone with Assaiante, plotting and discussing the team. He has a 3.5 average, majoring in economics. He has been dating a Trinity woman who grew up outside Philadelphia. He is probably the most well-known person on Trinity’s campus.

No one saw it coming. “In life the dots connect,” Assaiante said. “What happened, I just didn’t see coming. The dots didn’t connect. It was just an abhorrent moment of loss of composure. I just didn’t see any way that that would happen and when it was on top of us, we were just in the middle of damage control. I love this boy.”

The story went viral. Once the video of the match reached ESPN (don’t ask how), it went onto YouTube and reached millions instantly in a way that poor behavior in the past never did. People commented. People commented on the comments. It reached local news broadcasts, newspapers, radio. It snowballed. At one point Trinity was receiving a hundred emails an hour about it. In the first sixty hours after the incident, Assaiante got more than five hundred emails from people he didn’t know. Assaiante and Dave Talbott went onto ESPN. USA Today ran stories. It was national news.

For about five hours on the Friday night after the incident, there were just four items on the ESPN crawl at the bottom of the screen: one about Tiger Woods, another about Lindsay Vonn, a third about the USA hockey team and a fourth simply saying “Baset Chaudhry withdraws from singles championship.” That was it. He had become such a household name that ESPN assumed its viewers knew who he was.

Why did Chaudhry explode? We had a long conversation after the incident and he didn’t know for sure.

It was his last team match and he loved the team and was much more focused on winning a national team title than an individual one. If it had not been the clinching match, perhaps there would have been less emotion.

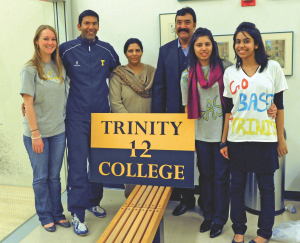

He was playing in front of his father, mother and two younger sisters. They had flown over that week and for the first time in his collegiate career they were watching him. His father had been a strong influence on him. Perhaps this put him on edge.

He was playing in front of his father, mother and two younger sisters. They had flown over that week and for the first time in his collegiate career they were watching him. His father had been a strong influence on him. Perhaps this put him on edge.

Moreover, all the taunting and yelling that he heard that afternoon, he was slightly unhappy that his family was having to listen to it. Over the years, fans had chanting of “USA, USA,” and “Go back and bomb Osama Bin Laden” and “Terrorist” and “Al Qaeda.” They had booed when he asked for a let. This was standard fare at collegiate matches these days (such harassing in Hanover at the Dartmouth v. Harvard match made headlines this winter). He had heard all that at matches before but he hadn’t heard anything like that with his mother and sisters and father present.

No doubt some of it came from the fact that he was exhausted by the expectations: being the #1 of the #1 fifty times is tough. He was aware of the history that awaited him. Another tight match won—it was cathartic and he wanted to yell.

He yelled also because he doesn’t like squash. He was kind of

pushed into it—cricket was his first love—and unlike the majority of the elite collegiate players in the past decade, he is not planning to play professional squash on the PSA tour. He is going to New York to work at Barclays Bank. In fact, he tells me that he might not pick up a racquet at all again—“they are locked up now,” he says. He might eventually join a club in New York, but squash is something that he will leave behind once his college career is finished.

Chan also provoked him. I watched their match in the Trinity v. Yale dual match in January at Payne Whitney. It was nothing out of the ordinary. Chaudhry chopped him up 11-2, 12-10, 11-5. But when Chan got off court, he commented loudly, “That guy’s got the biggest ass I’ve ever seen.” Then three or four players overhead Chan claiming that if he had won the third game, the match would have been his. People came up after to Chaudhry, asking him, “were you tired in the third? Was it a struggle?” It was so absurd, Chaudhry dismissed it.

At the nationals, there was more silliness. In the second game at the nationals, with the score at 2-2, Chan taunted Chaudhry after winning a point, coming up to his face, yelling and fist-pumping. Throughout the match, when Chaudhry would tin, he would sometimes audibly moan, “No.” Chan would then reply, “Yes.” “It was disrespectful,” Chaudhry told me. “No one had ever disrespected me like that, ever. Maurico, Sid, Harrity—these were tough matches, but they always played with class.”

Yet, it was bad sportsmanship and he made the right decision in stepping down from the intercollegiates. “It was very disappointing,” he says. “I am not going to try to defend my actions. It was such a pity it ended that way and I am truly sorry. It was the heat of the moment.”

But the oversized reaction says a lot—about the people who verbally sprayed him with obscenities after the match, about the hundreds of people who condemned him in chat rooms and blogs and comment spaces. Would we have felt this way if this had been a couple of preppy St. Grottlesex boys? Was this insane reaction derived in part subconsciously, because he was non-white, from a country where the U.S. is fighting a war?

We have seen this kind of misbehavior for decades in collegiate squash. No need to name names, but you know who you are. And flagrantly bad sportsmanship occurred just this season: there was some serious pushing and shoving—perhaps a punch thrown—in one of the Yale v. Harvard matches at their dual match. Two Ivy coaches got into each other’s grills and yelled at a dual match.

Is this a surprise? Today all sorts of athletes and fans behave much worse than Chaudhry did and they do it on television and in front of audiences of thousands. That doesn’t make it acceptable, just more understandable.

Interestingly, it doesn’t have to be this way. The College Squash Association doesn’t have a usable discipline system like they do in intercollegiate tennis, where warnings, points, game and match penalties are assessed. Many observers, Yale’s coach Dave Talbott in particular, long lamented the fact that the sportsmanship was so awful in the mid-1990s that the CSA had to resort to having referees for matches. When the players had to police themselves, by and large they behaved well. Now they pour vitriol on the refs (their teammates and opponent’s teammates), fling racquets, moan and curse. Perhaps the CSA should adopt what they do in tennis and have a roving umpire at dual matches who can do what coaches and players are not comfortable doing and actually apply penalties to poorly behaved players (or fans)?

In the meantime, a man’s life has been changed forever. He lost his chance at squash history. His fifteen seconds of bad behavior is now imprinted in the minds of millions; with the Internet, a fifteen-minutes of infamy is now permanent in a way. Barclays, it was rumored, was contemplating rescinding its job offer. He has received hate email. For a while he was worried about getting suspended or expelled from school.

Afterwards, Chaudhry did the right thing. Minutes after the incident, he apologized to the Yale team, Chan and the crowd at the trophy ceremony. The next day he decided to email a letter to all sixty-three CSA men’s team coaches which was forwarded to every one of their players: “For the last four years I have worked so very hard to be a perfect representative of the college game. I have won 6 championships, been a scholar athlete and have always tried to keep my contribution to our game positive. Yesterday in the heat of the moment with some of the contributing factors I lost my composure, and sadly it is being played out in a multitude of venues. This is heartbreaking for me, as I have never seen myself in that light, and am saddened to have to see over and over. I am a college student just like you. I am human and I hope to learn from this experience so that I can be a better man in the future

When you think of me as I leave college please try to remember my body of work and not just the last 15 seconds.” And he voluntarily stepped down from the intercollegiates.

Now Baset Chaudhry is walking away, perhaps the greatest player in intercollegiate history, with his head hung low.